I experience quietness as an incredible condition. Within the quietness of mind you hear a kind of deeper process, a deeper wisdom.

I remember at Harvard the rational mind was so highly valued and when somebody said, “I intuitively know it,” it was treated as a kind of weakness. I mean it was so sexist, it was absurd, you know? “Men think, women intuit,” as if it were such a horrible thing to intuit. In the course of these years I’ve seen that change, so that intuition is starting to be trusted more. The fact that you could have an understanding of things from a way of being in the universe that is more subjective than objective, that you’re not knowing it as material, you’re being it, and the action is coming out of it.

It all goes against our usual strategies for knowing and acting out of knowing. As Westerners we try to act from a place where we know we know, and to start to transform that so that the action arises out of the gestalt, which is far more than something you could know you know, you start to trust a certain quality of tuning to the harmony of things, and acting out of that.

I’ve seen that over the last many years I’ve had to retrain myself to trust that tuning, not to reject it.

The most gross example I had was being in Benares, India in the city of the dying, and having all of these lepers down by the ghat, the place by the river, and they had all had their begging bowls, and I came along with change, and different denominations, and I started down the line, and I had this handful of paisa and rupees. I looked at the first person and it was somebody who had half their face eaten away. I had a thought of, “My God half the face is eaten away,” so I gave him 50 paisa, but the next one was a women who had her arms eaten away, and I thought, “Oh my God,” and I gave her 10 rupees, and I realized it was an impossible way of going about it. There was no way that I could rationally make a decision as to who should get what, and at that point I sort of just let go. I went down and met each person, and then just did something without asking myself what I was doing.

If you have heard the story you know that they actually have kind of a union, and they share all their money. So it was just my trip, but it was a great teaching experience from my point of view. It gave me a kind of incredibly gross or bizarre example of what we’re doing all the time, of making these kinds of decisions that are so much more complex than our analytic mind can handle.

We are so busy trying to hold on to that part of us that thinks we have free will responsibility, and that we’re choosing and all that – and I think that is such a crock actually. I know most of you won’t agree with that, but I really have to say it, even as dramatic as that sounds. I just don’t think we have the choices we think we have.

They aren’t coming out of a vacuum, they are all part of lawful, unfolding phenomena, and everything is lawfully interrelated to everything else, and so if you could stand back far enough, you would see yourself unfolding, just like a flower is unfolding – and that flower could be saying, “I think… shall I open my flower or now?” But you know, there are a lot of forces determining a lot of that.

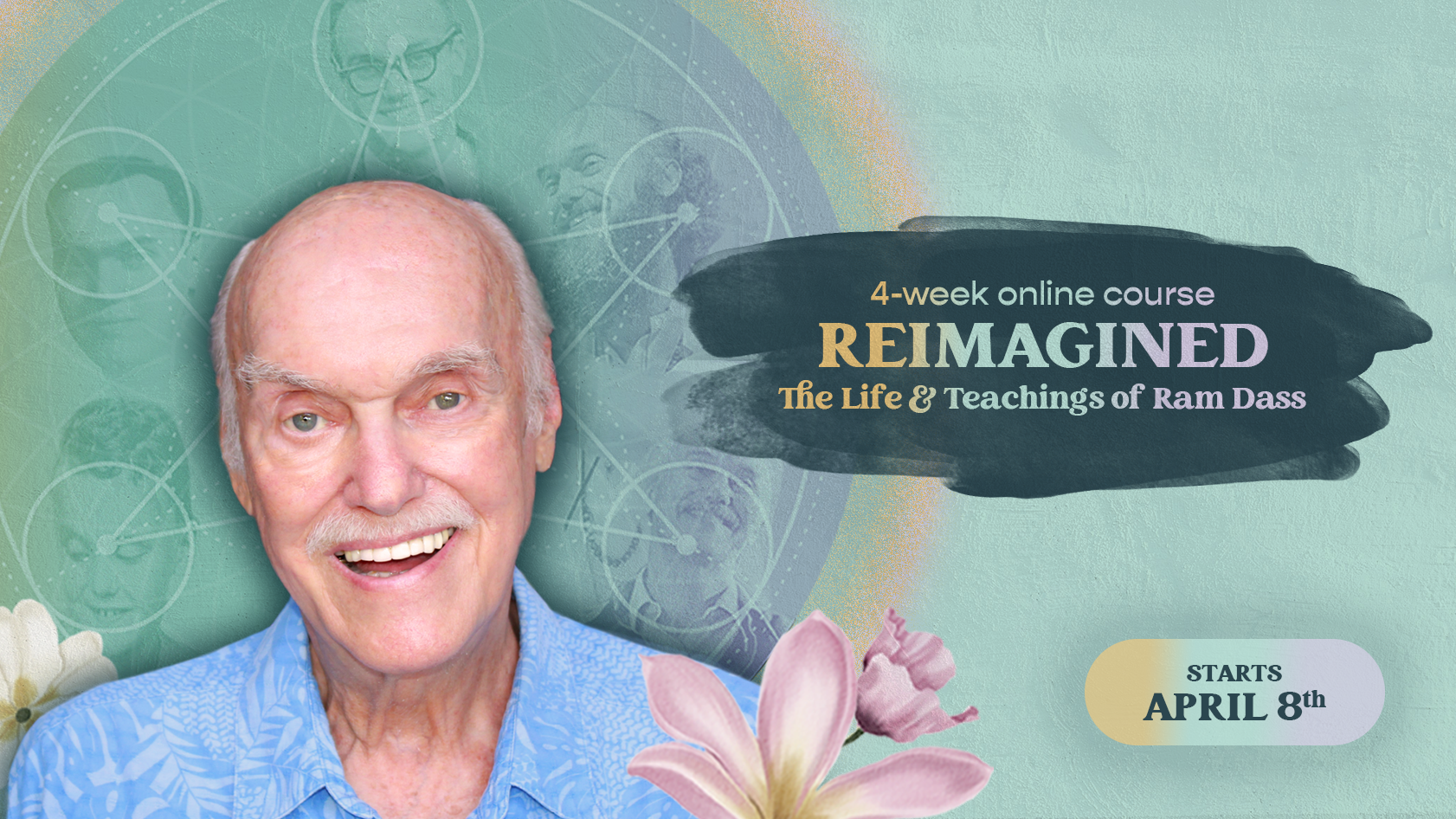

– Ram Dass